Dialogue tags (with comparison to Flight of the Heron)

This section should be compared to the section on dialogue tags in The Flight of the Heron. While I wouldn’t describe the prose style of Kidnapped as exactly utilitarian, one gets the impression when comparing the two books that it is certainly more informal, much less ornamented and perhaps less crafted-feeling than that of Flight of the Heron. Investigating both authors’ use of dialogue tags confirms this, and reveals various details of how it works at the sentence level.

There are 588 uses of the word said in Kidnapped. But—even before we get to different words used in place of said, for which see below—that’s not the whole story, because, while the book is generally written in the past tense, many of the dialogue tags are in the present tense and use says instead. There are 164 sayses in the book. As with Flight of the Heron, I went through and counted how these saids were used, including sayses as well; here are the results:

| ‘Dialogue,’ said character | ‘Dialogue,’ character said | Character said, ‘Dialogue’ | Said character, ‘Dialogue’ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| With name | 135 | 2 | - | - |

| With pronoun | 282 | 41 | 1 | - |

| With epithet or title | 44 | 1 | 1 | - |

| ‘Dialogue,’ says character | ‘Dialogue,’ character says | Character says, ‘Dialogue’ | Says character, ‘Dialogue’ | |

| With name | 41 | - | - | - |

| With pronoun | 103 | 1 | - | 1 |

| With epithet or title | 14 | - | - | - |

Another 81 saids and 4 sayses are not in dialogue tags.

Compare this to the equivalent table for Flight of the Heron. Stevenson’s most-used construction, in both the past and present tense, is ‘Dialogue,’ said pronoun. This is something I associate with fast-paced adventure writing of the late nineteenth century—E. W. Hornung is also fond of it (the Raffles stories collectively have 430 said pronouns and only 195 pronoun saids)—and I’d already noticed Stevenson’s preference for it, though I hadn’t realised that it was quite such a strong preference! Broster, writing in a slower-paced and more formal style, barely uses it, and the difference here is striking.

The most obvious difference, of course, is Stevenson’s use of present tense in dialogue tags, something Broster never does. I think this shifting into present tense in a narrative mostly in past tense is another feature of nineteenth-century adventure writing, though I’m actually struggling to find many examples searching for it in other books, so perhaps that’s an impression I got purely from Stevenson! Perhaps more relevantly, it’s a construction often heard when someone is telling a story in informal speech (‘so I sez to her, I sez...’); thus it particularly suits a book narrated in the first person, and it gives a sense of informality and directness and one of immediacy, suitable for an exciting story full of fast-moving action. Stevenson doesn’t often do it outside dialogue tags, though some other nineteenth-century writers do (Thomas Hughes, author of classic boys’ school story Tom Brown’s School Days (1857), sometimes shifts into present tense for an entire passage to convey the urgency and excitement of a particularly dramatic episode). The preference for the ‘Dialogue,’ said/says pronoun construction is stronger in present tense—64.4% of sayses appear in this construction, versus 55.6% of saids—and this is largely at the expense of ‘Dialogue,’ pronoun said/says, which is moderately common in past tense but barely used in present tense.

Then Stevenson uses pronouns, rather than names or epithets, much more than Broster. One reason for this is obvious: Kidnapped is narrated in the first person, and thus in most conversations between two characters the narration will use different personal pronouns to refer to them, whereas that’s often not the case with the third-person narration in Flight of the Heron. It’s noticeable that the frequency of names and epithets increases sharply when two male characters other than David are talking (e.g. Alan’s conversations with Captain Hoseason, Robin Oig and Ebenezer), whereas conversations between David and another male character often alternate between said I and said he for paragraphs on end, and conversations including female characters likewise use said she alongside both. When Stevenson doesn’t use a pronoun, his preference for names over epithets is stronger than Broster’s, with a ratio of roughly 3:1 between them, compared with 2.4:1 in Flight of the Heron.

Having investigated said, I then looked at alternatives to it. Here are some of Stevenson’s most-used ‘said bookisms’:

| Word | Uses (past tense) | Uses (present tense) |

|---|---|---|

| cried/cries | 109 | 24 |

| asked/asks | 68 | - |

| returned/returns | 27 | - |

| continued/continues | 24 | - |

| replied/replies | 10 | 2 |

(These numbers come from doing a simple search of the text for each word, so they will include uses in contexts other than dialogue tags).

Though there are fewer different words in here—in keeping with his more frequent use of said, Stevenson is much less keen on alternatives than Broster—this actually looks oddly similar to the equivalent table for Flight of the Heron. These are mostly words that describe the function of the dialogue in the conversation rather than the speaker’s manner, with one exception, cried/cries—Stevenson’s favourite alternative to said/says. Broster also uses mostly ‘functional’ said-alternatives with one exception, in her case exclaimed. Stevenson never uses exclaimed (whereas Broster uses cried only 16 times, compared with 43 exclaimeds), and I think this choice again illustrates the difference in their writing styles: Stevenson uses a short, informal word while Broster chooses a longer word with a Latin prefix. Also interestingly, cries is almost the only dialogue tag other than says which Stevenson uses in the present tense; a word describing a particularly urgent manner and the present tense, both making for more exciting and immediate-feeling prose, go together.

Next, I went though some dialogue-heavy scenes from different parts of the book and examined the use of dialogue tags in more detail. Having already noted the importance of the first-person point of view, I picked a balance of conversations including David and other characters:

- David and Ebenezer in chapter 3 (full chapter)

- Alan and Hoseason in chapter 9 (from ‘I’m vexed, sir, about the boat,’ to ...and left me alone in the round-house with the stranger.)

- David and Alan in chapter 18 (full chapter)

- David, Alan and the lass at the change-house in chapter 26 (from ‘What’s like wrong with him?’ to ‘I’ll find some means to put you over.’)

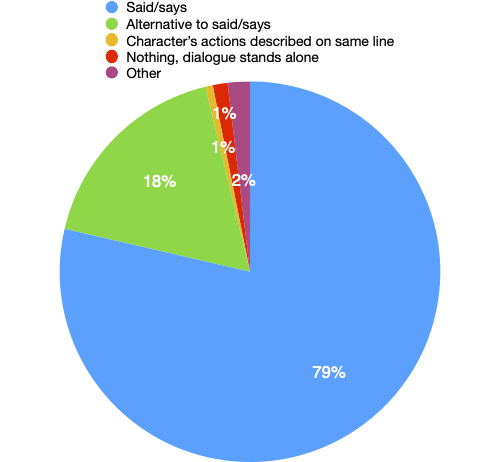

As before, I counted whether each piece of dialogue was accompanied by said/says, an alternative to said/says, or either of two alternatives to dialogue tags: describing the speaker’s actions on the same line, and letting the dialogue stand alone with only the context to make it clear who’s speaking. (The ‘other’ category mostly contains constructions where the dialogue itself rather than the speaker is the subject of a verb, as in ‘Dialogue,’ was the next thing he said.) Here are the results:

| David and Ebenezer, c.3 | Alan and Hoseason, c.9 | Alan and David, c.18 | Alan, David and the lass, c.26 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dialogue tag with said/says | 32 | 17 | 43 | 33 | 125 |

| Dialogue tag with alternative to said/says | 8 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 28 |

| Character’s actions described on same line | - | - | - | 1 | 1 |

| Nothing, dialogue stands alone | 2 | - | - | - | 2 |

| Other | 2 | 1 | - | - | 3 |

This confirms what the count of saids/sayses and the list of alternatives have already suggested: Stevenson’s dialogue tags are not very varied! He uses said or says nearly four-fifths of the time, and most of the last fifth are alternatives to said/says; this is in contrast to Broster, who uses each of the four constructions counted here with more than 15% of dialogue lines. Once again we see the difference in their styles. Stevenson uses plain but punchy language to drive the action along, rather than meandering in rich description and linguistic ornamentation as Broster does: hence we get simple said with a large majority of lines of dialogue, relatively few ‘said bookisms’, little use of the creative and often ironically humorous epithets which Broster enjoys (where Stevenson does use epithets, they tend to be straightforward ones like ‘the captain’ and ‘my uncle’), and the frequent slips into present tense as a relatively plain but effective way to heighten the pace.